Artists soon joined the poets in championing the creative and political potential of the unconscious, dreams, and the irrational, Jean (Hans) Arp one of the first among them. In Max Ernst’s nocturnal and stylized group portrait, Rendez-vous of Friends (1922), Arp joins Giorgio de Chirico and Ernst himself as the only three living artists among many more writers, led by Breton, Paul Éluard, and Louis Aragon.

Arp was a pioneer of a proto-automatism in the teens and early ’20s, before Surrealism proper, with drawings such as the ink from the series Terrestrial Forms (1917), but how could such a free and intuitive approach be applied to molding plaster?

And what role does plaster play for the sculpture of Arp? Apart from some rudimentary, early instruction, it was not a medium of his iconoclastic Dada youth, which focused on collage, embroideries, and wood reliefs. Arp began using plaster, and plaster casts, when he turned to the three dimensional in the early 1930s, and it remained central until the end of his career in 1965.

Arp’s description of modeling in plaster is curious, yet notable, as it seems to sidestep artistic volition:

“This is the mystery: my hands talk to themselves. The dialogue is established between the plaster and them as if I am absent, as if I am not necessary. There forms are born, amicable and strange, that order themselves without me. I notice them, as if one notices human figures in clouds.”

In negating artistic will, Arp opens the door to tapping the subconscious mind, as the Surrealists emphasized.

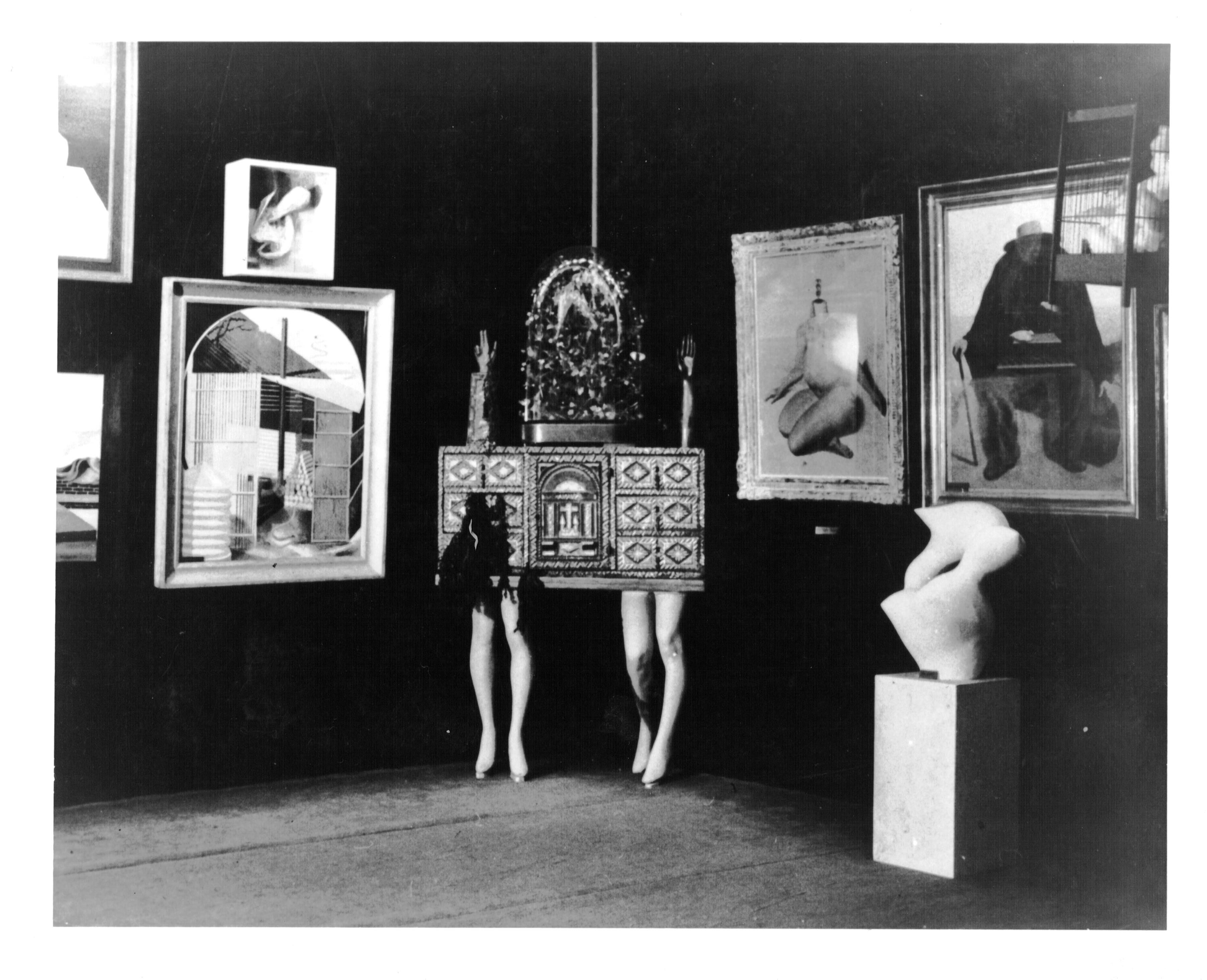

Arp’s exploring the possibility of a free automatism in three-dimensional form is unexpected, as Surrealist automatism generally is thought of in terms of two-dimensional media, but Arp’s turn is part of a general Surrealist trend into sculpture in the 1930s. The Surrealist exhibition at the Galerie Pierre Colle in June 1933 was an early manifestation, and Arp exhibited two of his first plasters in proximity to a sculpture by his old friend Max Ernst, presented with sculptures by Alberto Giacometti, Salvador Dalí, and others. Arp later exhibited two plasters plus a relief and a mannequin in the landmark International Exhibition of Surrealism of 1938. While most Surrealist sculptors pursued the object, and readymade or found materials in the mid-1930s, Arp stayed on track with the possibilities of direct engagement with simple plaster.

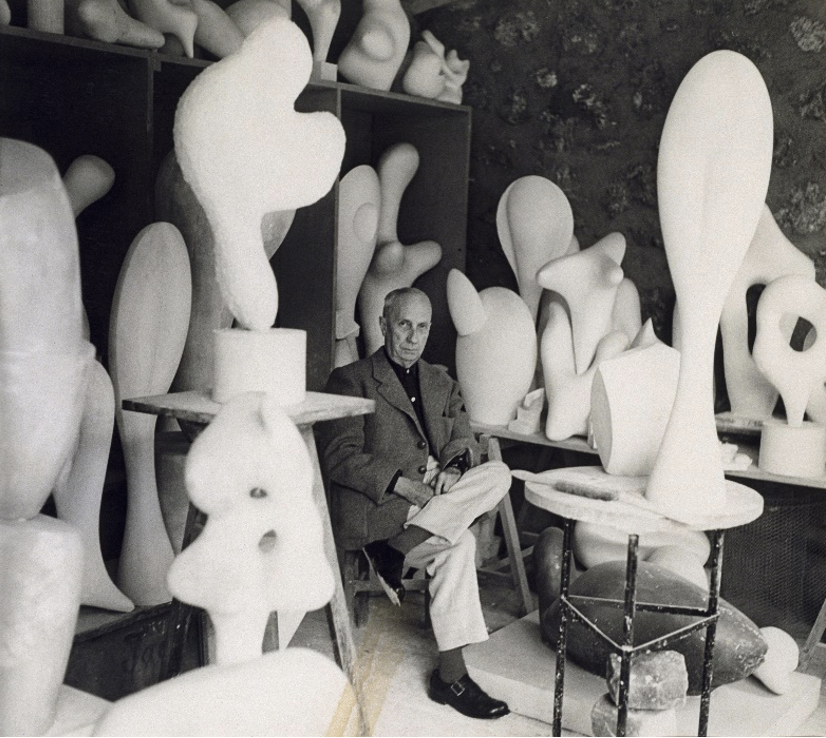

The ease of casting in plaster enabled Arp to explore a multiplicity of options. He could preserve a cast of the current state of his forms, then continue to rework, add to, or cut from them, creating a new variant that itself could be cast again. Plasters thus multiply in geometric progression, as the crowded shelves of his later Meudon studio storage testify. Interestingly, he did not edition such casts, though he at times exhibited them or gave them to friends. Rather, plasters would be used as the basis for creating bronze or marble versions to be marketed. It is as if the plasters were Arp’s research division, separate from the sales and marketing department.

Plaster surfaces could be easily built up additively, yet also easily cropped or cut. Early examples include sculptures literally in pieces, united by the visual similarity of their surfaces. Sculpture to be Lost in the Forest is an important three-part early experiment. The work comprises two smaller, similar-sized rounded forms, and one larger one placed horizontally. These are not fixed, but rather rearrangeable, usually with the two smaller placed on the larger. The title stems from walks in the Meudon forest with Arp’s friend Camille Bryen, during which small sculptures were left behind. Here the title becomes ambiguous, apparently a command to the viewer which, if followed, would mean that the piece is ultimately to be returned to nature. In this case, Arp did not follow the instruction, but rather kept the work—or a cast of it—in his studio.

Following on its 2018 exhibition The Nature of Arp, the Nasher Sculpture Center is one of several institutions selected by the Stiftung Arp e. V. to receive a group of works from the foundation’s dispersal. This donation of 21 plasters and three bronzes by the artist constitutes the largest gift to the Nasher since its founding. It also includes an in-depth, chronological representation of Arp’s sculptures from the 1930s to the 1960s. The sculptures spur many associations, among them:

Star’s (1939) title directs us to one reading, emphasizing the three celestial points atop. Yet its irregularities, as well as the central void, open up suggestions of the physiognomic. The surface of this cast appears to be covered with small crosses—marks that suggest this plaster was pointed up for an enlarged cast.

Ptolemy (1958) is a series of three works, the latter two in the Nasher’s collection being made after his return to Greece in 1955. They are among the most abstract, balanced, and symmetrical of Arp’s sculptures. In Ptolemy II (1958), the linear volumes enclose the central space, forming an upright ovoid. From some views the forms open up; in others the overlapping of the lines flattens the whole.

Scale also becomes an element in play with casting. Gnome Form (1949) is small, a little over 15 inches high—a suggestion of an upright body and head, with the nub of a projecting arm. “Upon waking I found on my sculptor’s turntable a small mischievous shape, perky and rather obese, like the belly of a lute. It seemed to recall a goblin. And so that’s what I named it,” wrote Arp, again attributing volition to the residue of dream. This “goblin” was giganticized for a 10-foot public commission, retitled Cloud Shepherd.

Classical allusion continues in Venus of Meudon (1956), where Arp substitutes the location of his studio outside Paris for the classical “de Milo.” Thus prompted, we can read the swelling lower portions of this Venus as alluding to a feminine torso—a theme found in many of Arp’s later works.

Sculpture’s materials and processes pose inherent challenges to automatism; however, Arp devised alternatives working by intuition and inspiration. Instead of utilizing sketches as a means to tap into unconscious action, he proceeded by touch as much as vision. Arp consistently explored biomorphism and free form in his plasters above all, opening up the possibility of a sculptural automatism, and the persistence of Surrealism, into the 1960s.

IMAGE TOP: Installation view of Exposition internationale du surréalisme, Galerie Beaux-Arts, Paris, 1938. Photo by Man Ray. © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2024

IMAGE MIDDLE: Arp in his studio in Clamart, 1957. Photo by André Villiers, courtesy of Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth

IMAGE BOTTOM: Max Ernst, Rendez-vous of Friends (A Friends Reunion), 1922. Oil on canvas. 51.2 x 37.4 inches (130 x 95 cm). © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris