The Trinity River that runs through North Texas has seen its share of scheming. In the 1890s an unrealized proposal was submitted to broaden its banks to accommodate a shipping channel, creating the “Port of Dallas.” In 1928 the river was straightened to prevent flooding and allow for downtown development. Today (and for the last two decades) it is the center of a grand fundraising effort to build a 250-acre city park. Before these man-made, Texas-sized dreams, it was the Akokisa, running through the Blackland Prairie, swelling and drying along a snake-like path. A Dallas-native artist and activist takes us along their search for the river’s persona.

DALLAS is Apache, Comanche, Kiowa, Kiikaapoi, Tawakoni, and Wichita land, among others.

Growing up, my family shared captivating tales about the Trinity River. My grandparents migrated to Eagle Ford (known locally as Ledbetter) in the 1940s, leaving Lockhart and Waco, Texas, behind. They spoke of unpaved roads, a tight-knit community, and how salamanders would gather under streetlamps. During the 1950s, the West Dallas salamanders reigned over the nocturnal streets, and the Texas prairie crawfish were plentiful, occasionally finding their way onto dinner tables. Yet, by the 1980s, I spotted only one blue crawfish in the Trinity River, and since then, they have almost vanished completely. Alongside Afrika Bambaataa’s “Planet Rock” playing on the neighborhood boomboxes, the nighttime symphony belonged to the Gulf Coast toads. The summer nights were filled with a warm breeze and their chorus, but sadly their sounds have mostly been displaced over time.

Flowing through Dallas, the Trinity is Texas’s longest river, spanning 710 miles. In 2018, efforts to revive the indigenous name Akokisa began, aiming to engage the community and dispel colonial myths. Jerry Hawkins of Dallas Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation uncovered the correct indigenous name, “Arkikosa,” previously attributed to the Caddo Nation. However, in October 2022, Dr. Timothy K. Perttula and Alaina Tahlate of the Caddo Nation provided a report that clarified that the term “Arkikosa” was not used by the Caddo people. Instead, it was a misspelling or corruption of the word “Akokisa” (or “Orcoquisa”). The word translates to “river people” in the language of the Atakapa tribe, who used to live near the Gulf of Mexico and are currently seeking federal recognition.

Once I learned the River’s name, my connection with our natural surroundings continued to evolve, leading me to investigate communities that won personhood for water—a legal designation that bestows a river with rights such as the right to flow, or the right to sue. The Whanganui River, Ganges River, Klamath River, and Vilcabamba River, and more have won legal personhood, with many more seeking the status. This movement led me to pursue a first-person narrative with the Akokisa.

Grammatical Note: When speaking of the River, I use pronouns that reflect the movement of water without assigning a gender, using “they/them” to explore their fluidity and animacy—a shift inspired by Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Kimmerer, a scientist and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, explores how the English language lacks the adequate vocabulary to respect the animacy, or sentience, of nonhuman beings. She writes, “In Potawatomi 101, rocks are animate, as are mountains and water and fire and places. Beings that are imbued with spirit, our sacred medicines, our songs, drums, and even stories, are all animate.” In English, our grammar reduces a nonhuman being to an “it,” or we assign gender inappropriately as he or she. Where are our words for the existence of another living being?

To connect with the water and their personhood, I began kayaking their path through Fort Worth, Arlington, Irving, and downtown Dallas, mapping the waterways. While visiting the River to listen, questions arose: Who embodies the essence of water? If water could speak, what stories would they share? What memories might the West Fork and Clear Fork River bodies carry when they meet the grand Akokisa River in Dallas? I read about the Dallas floods and how Akokisa had been moved three times to accommodate growth. I was reminded of a 1986 talk at the New York Public Library where novelist Toni Morrison describes how the Mississippi River was straightened out to make room for housing. She remarks, “Occasionally the river floods these places. ‘Floods’ is the word they use, but in fact it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.” I wanted to investigate these memories.

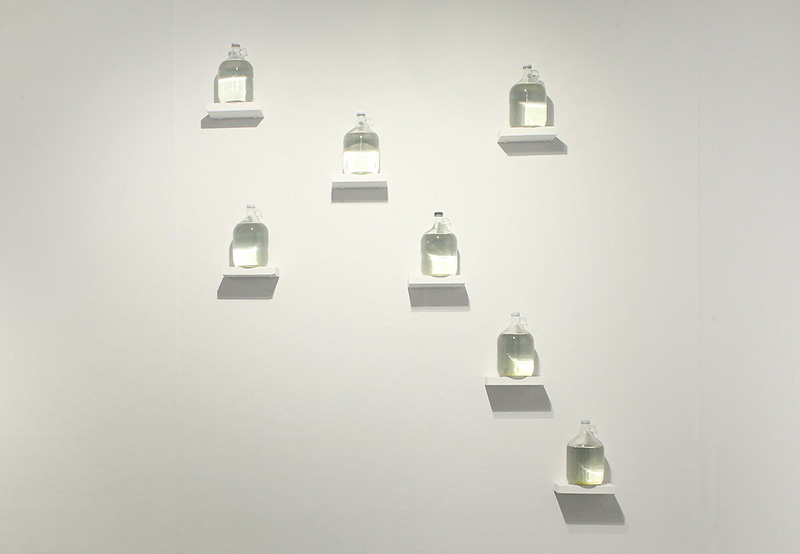

In 2021 I began working on a collection of artworks that would tell the story of the Akokisa, focusing on their personification through visuals and sounds of the River. Accompanied by writing, historical timelines, relief prints, sculptures, and video, I created an installation of jugs filled with river water, titled The Grammar of Animacy. In this project, I conducted simple water quality tests to explore the River’s overall wellness as a body of water, collecting water samples from seven different areas in Dallas. Stored in glass gallon jugs and installed on the wall in a cascading pattern, each specimen’s clarity revealed various degrees of coloring based on the water’s location, but from a distance, and in photography, they appear clear and innocuous, requiring close inspection and further reading. Alongside the jugs I provided a map with a QR code to encourage curiosity in fellow river people.

Like much of my work, the installation of jugs served as a tangible way to activate facts of local water memories, but the finished work is a mere piece of the larger art of searching.

For the past five years, I have closely observed and listened to the River, paying attention to their movements, stillness, fluidity, and reflections. The mutable nature of water as a transconsciousness permeates my work, and it has inspired me to delve deeper into exploring the fluidity of water and the body as an autonomous being. The solutions to today’s problems are coded into the adaptability of nature if we can perceive beyond our human-centered supremacy.

The Akokisa welcomes you to their banks with open arms.

Editor’s note: The Akokisa project has become a citywide movement, blending immersive art forms to connect with natural ecologies and history. Indigenous leaders have been included in the efforts to rename and acknowledge the Akokisa, moving beyond land acknowledgments and toward sovereignty in Dallas.

Water has a memory/Remembering by Ángel Faz, made in 2021 for New Stories: New Futures at Pioneer Tower at Will Rogers Memorial Center. Images courtesy of the artist.