Running water always beckons. And then bears our thoughts away. And I suspect the only difference in this regard between the Ganges, say, and temporary rivulets of rainwater along the curb is the depth and breadth of thoughts transported. Those of children, I imagine, in the latter case. Who, drawn to kneel too close to the street, will watch the leaves like boats and sense their tiny selves departing. Look, oh look, where does it go? And that’s the question. Or the riddle. Who can say? And even with the water gone—evaporated, buried—there remains that question. Once your leaf goes out of sight, it may go anywhere.

Such small exhilarations must have floated down the creek once called the Dallas Branch, now buried, flowing under the Nasher Sculpture Garden and much of downtown Dallas. Dark and culverted and thoughtless. How peculiar: just as famously unwanted high-rise-mirrored light glares down onto the premises, this unremembered darkness flows beneath. We ought to think about it. First of all—although it might seem trivial— to note how, unlike poetry, music, painting, which are weightless, sculpture tends to hold its ground. At least in principle. It fastens on the world in a sort of compromise. Without the separation that’s required to present that broader reimagining. That altering of the air of our experience that even the simplest grade school landscape can achieve. Of course, of course, there are and always have been mixings, violations—we don’t need no stinkin’ categories. Yet they’ve always been there and are meaningful. Sometimes those Paleolithic cave wall paintings take advantage of a happy undulation in the rock to bring some spectral creature out to us. It startles. And you see what’s gained and lost—to our eyes anyway. It’s breathing our air now. The slightest sculptural inflection joins our world and leaves that other.

Such small exhilarations must have floated down the creek once called the Dallas Branch, now buried, flowing under the Nasher Sculpture Garden and much of downtown Dallas. Dark and culverted and thoughtless. How peculiar: just as famously unwanted high-rise-mirrored light glares down onto the premises, this unremembered darkness flows beneath. We ought to think about it. First of all—although it might seem trivial— to note how, unlike poetry, music, painting, which are weightless, sculpture tends to hold its ground. At least in principle. It fastens on the world in a sort of compromise. Without the separation that’s required to present that broader reimagining. That altering of the air of our experience that even the simplest grade school landscape can achieve. Of course, of course, there are and always have been mixings, violations—we don’t need no stinkin’ categories. Yet they’ve always been there and are meaningful. Sometimes those Paleolithic cave wall paintings take advantage of a happy undulation in the rock to bring some spectral creature out to us. It startles. And you see what’s gained and lost—to our eyes anyway. It’s breathing our air now. The slightest sculptural inflection joins our world and leaves that other.

Is there something to be made, then, of the Nasher Sculpture Garden with a blind creek running under and a blinding light above? Sounds pretty sweet, you must admit. I suggest it serves to emphasize how captured, how discovered, we are here upon the surface of the world. Among the sculptures, how like sculptures (think George Segal) of ourselves. How stopped. How paused within the moment as if waiting here beside the buried stream that runs within us.

Running water seems to beckon Mary Miss like no one else, I think. The day we met at the Nasher for lunch, she’d already been out afoot and alone, without bearers, guides, or provisions, to trace the buried course of the Dallas Branch to its rumored emergence (its “outfall”) into the Trinity. She’s been engaged to make some sculptural sense of this. But how to peer down through the accretions of a century to discern the deeper facts? Old Sanborn fire insurance maps, if old enough, will show a sinuous band of blue through ghostly outlined, mostly vanished combustible structures. By the 20s it is vanishing as well. By 1950, barely a trace. But off she goes, pretty much by feel for the topography, she says, which I find somewhat mystifying. (I imagine Mary striding through the lobbies of those massive office towers—in one door and out the other like a ghost, herself.) At some point she abandons topographic intuition just to make it under the highway toward the Trinity by whatever rectilinear route presents itself to bring her, after an hour and a half, to a place behind some building where she might ascend to the top of the levee and discover—as Cortez, “with a wild surmise”—a clear and narrow sweep of water flowing away to the greater stream. And, dang, if it didn’t turn out to be it. The hydrological authorities confirmed. The buried, blinded Dallas Branch flowing out of oblivion into the light. And all before lunch.

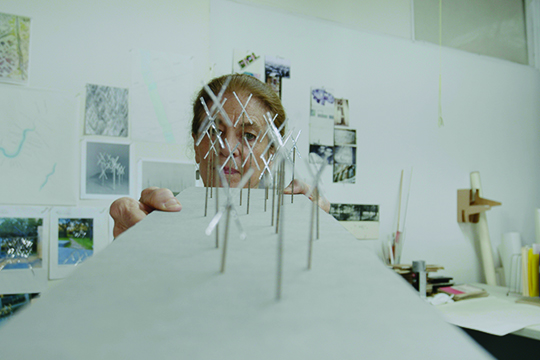

She has arranged to have erected a wooden mock-up of the stainless-steel procession, tracing the vanished course of the stream across the garden. Twenty-one poles surmounted by oblique Xs. Stations, as they seem, in some strange ritual or game. She seems to play—as a child, in the very best sense—with the physical facts of the earth. Like Smithson and Goldsworthy, in the sandbox of the world to shove it about and see what’s there. Oh, look: here’s consciousness and memory and loss.

I ask if we might see that drain or whatever it was—some kind of opening she mentioned having noticed during earlier explorations, in the corner of the deepest parking level of an adjacent building. Way at the bottom there was water. I had read about London’s buried tributaries. And how, lost to the surface since medieval or even Roman times, one still may glimpse through certain ancient grates in streets or basements, ancient waters, ancient process running through. So off we go—my wife, the artist Nancy Rebal, Mary and I.

So many levels. Such a promising descent into an unlocatable sound of rushing air and a high-pitched squeal. A number of scary movies come to mind. Who parks down here? Ahead is a concrete wall emblazoned with broad, diagonal black and yellow stripes. At one end of which, in the corner, attended by vertical structures of obscure electrical function, is the hole. The drain. The pit. Whatever. The entire arrangement rather like some grim Tom Sachs construction. I suspect this is the terminus. The point where art grades into something else. It is a complicated hole. Protected by two halves of a four or five-foot disk of steel tread plate—one half dragged somewhat to the side so we can see down in where a plastic pipe, steel chains, and cables drop into the agitated water maybe 15 feet below. The mating edges of the tread plate have these bites torched out to accommodate the plastic pipe and all that dangly business. What in the world is being addressed down there? Or appeased? Here Mary worries me—she’s bending so far over for a picture of the water. In those movies, we all know what happens next. The rush of air. The constant squeal. Okay, we’re done.

Mary wants to expand the piece, the idea of the piece, beyond the Sculpture Garden. To bring the whole extent of the buried creek into it. She’s returned to New York but has emailed me a current map of the area overlain by the course of the stream with 13 circled points along it where she imagines some sort of markers might be placed to encourage pause and contemplation. Maybe a QR code as well, to access others’ contemplations on the matter.

So, what is the matter? Just the dazzle, I suppose. Of the concrete moment. Even a buried stream still beckons—but you have to squint through so much glare to find it. Lean precariously, like Mary, over the edge to think your way down to it. Then allow your thoughts to float along it in the dark toward a larger thought, perhaps, of history. Beneath these modern town homes, well beneath (sites 1 through 4), are weeds and mud and grassy banks, mosquitos—quite a few of those, I’m told—all sorts of frogs and insects, all the natural croaks and buzzings you’d expect along the creek to mingle with the gentle clatter of domesticity nearby. And in the city, of all places—the unmediated, impolite contingency of life through open windows to impinge in subtle ways upon the general mood, the quality of dreams, the feel of sheets.

Let us imagine—even passing beneath the freeway, as we must—a Wind in the Willows population. In those days before the blinding present moment, river creatures had the gift of speech, you know. So pause and listen as we arrive in the vicinity of the Nasher itself (sites 5 and 6). Be still as statues. Close your eyes and listen for, or attempt to sense at least, past all the traffic noise and such, the water moving and the creatures that would surely have inhabited, more clearly and immediately than now, the stories told a hundred years ago to children in their beds.

The older maps—those marvelous Sanborn fire insurance maps that through the years so colorfully plat our life in terms of its combustibility—have it simply marked as “shallow stream” (1899) or “small creek” (1905). By 1921 it’s the “Dallas Branch.” In any case, in size somewhere between the Ganges and that trickle by the curb. It really doesn’t take too much to let the wilderness, the impolite contingency, pass through. Be felt to pass. Especially as the city starts to gather into itself and mostly frame (combustible) homes press in. A thin riparian order holds: your cedar elm and cottonwood, hackberry, willow, sycamore. Your Cherokee sedge and switch grass, prairie cord grass (oh, be careful walking through bare-legged), and marsh fleabane (aromatic, purple-flowered). Fish. All kinds of edible fish. And audible frogs. Can you imagine in the spring and summer evenings through those screened but open windows—kitchen windows, bedroom windows—cricket frogs that sound like marbles clicking together, leopard frogs’ repetitive croak, the chorus frogs like raking your thumb across a comb, and eastern narrow-mouth toads that sound like bleating lambs, like little lost lambs out there somewhere. And all out there somewhere. That “out there somewhere” running through like that, so close.

That’s what we need to think about, proceeding west on Field Street and back under Woodall Rogers toward the American Airlines Center, all those parking lots and parking lots to come (sites 7 through 10), how “out there somewhere” still runs somewhere under parking lots—in some sense worth considering, regretting. Then down—you feel it tending down—into that district once “Industrial,” now “Design” with shops and galleries (11 and 12), to Levee Street, from which, along in here somewhere, she made ascent to her discovery.

Then back to the south 3,000 feet or so to an address on Dragon Street which, it has somehow been determined, is the point (site number 13) where the Dallas Branch and all its floating leaves, that represent our tiny selves, once emptied into the Trinity River, in its earlier course before the great rerouting, flowing southeast to the Gulf, whose bathwater-gray receives us all in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, at last.

Mary Miss Stream Trace: Dallas Branch Crossing part of Groundswell: Women of Land Art will be on view September 23, 2023 - January 7, 2024

Images:

FROM TOP: Mary Miss in her studio / New York, New York, 2023. Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos.

Site 12: The outfall of Dallas Branch into the Trinity River / Dallas, Texas, 2023. Photo: Nan Coulter.

Mary Miss in her studio holding a model of Stream Trace: Dallas Branch Crossing / New York, New York, 2023. Photo: Oresti Tsonopoulos.

Mary Miss in her studio showing drawings and maps in preparation for her installation at the Nasher / New York, New York, 2023. Photo: Adrienne Lichliter-Hines.