On the morning of June 12, 2020, a man dressed in a long black tunic and cap entered the Musee du Quai Branly, a museum in the middle of Paris, and pulled a sculpture off its base. As he headed for the door, he spoke to the mostly empty galleries: “I’m taking back to Africa everything that was pillaged while African blood was being shed,” he said. The man, Mwazulu Diyabanza, is a Congolese artist and activist, and the sculpture he took was a carved wooden funeral pole from Central Africa, about three and a half feet high. Like a headstone, funeral poles are still used widely across the continent to connect the bodies of the deceased with the land of the living. Diyabanza didn’t make it out the front door before the police arrived, but when they did, he asked for their help in finding the real thief: their employer, the French government, who stole the many thousands of objects at Quai Branly over 130 years of colonial rule. For Diyabanza, the funeral pole was a spoil of war. It was also just one of an estimated half a million objects taken from Africa during the colonial era, scattered across public collections in Europe.

If works of art could speak, what kinds of stories would they tell us? This isn’t a rhetorical question. Earlier this year, while developing Precious Cargo, a podcast series about the journeys of works of art, I began conducting research on the provenance, or origins, of art in various public collections. What I learned has been ringing in my ears ever since. So many of the objects taken by colonial violence are still on display in European and American museums, crying to be set free. Their cultural significance has been overdetermined by the traumatic circumstances of their plunder.

On a recent visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, I found myself in the Khmer galleries looking at a regal, life-size sculpture of a female deity from Angkor. Carved in reddish stone sometime in the 10th century, it is among the finest examples of ancient Cambodian sculpture, so influential to the region, that I had ever seen. The goddess is missing her hands and feet–a common feature of ancient sculptures I might have ignored, had I not already known that she was donated to the museum in 2003 by Doris Weiner, a disgraced dealer who acquired the sculpture through an international trafficking ring of looted antiquities. The deeply gouged ankles were almost surely where this goddess was hacked off her base in a Cambodian temple. Many of the Khmer artworks in museums like the Met and the British Museum were violently extracted from temples under the Khmer Rouge, whose genocidal reign in the late 1970s resulted in the deaths of an estimated 2 million people. In some cases, the black market in antiquities helped fund the military junta. Studying the wounded goddess, it was hard not to think of the bodies the Khmer Rouge maimed as a kind of collateral damage. How many of the families on their Sunday stroll through the Met galleries could sense her pain?

On a recent visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, I found myself in the Khmer galleries looking at a regal, life-size sculpture of a female deity from Angkor. Carved in reddish stone sometime in the 10th century, it is among the finest examples of ancient Cambodian sculpture, so influential to the region, that I had ever seen. The goddess is missing her hands and feet–a common feature of ancient sculptures I might have ignored, had I not already known that she was donated to the museum in 2003 by Doris Weiner, a disgraced dealer who acquired the sculpture through an international trafficking ring of looted antiquities. The deeply gouged ankles were almost surely where this goddess was hacked off her base in a Cambodian temple. Many of the Khmer artworks in museums like the Met and the British Museum were violently extracted from temples under the Khmer Rouge, whose genocidal reign in the late 1970s resulted in the deaths of an estimated 2 million people. In some cases, the black market in antiquities helped fund the military junta. Studying the wounded goddess, it was hard not to think of the bodies the Khmer Rouge maimed as a kind of collateral damage. How many of the families on their Sunday stroll through the Met galleries could sense her pain?

“Trauma travels in the body, it travels in space, and it travels in objects,” the artist Rayyane Tabet told me during an interview for Precious Cargo. We were discussing his 2019 exhibition Alien Property, which investigated the provenance of several ancient tablets from Tell Halaf, Syria, in the Met’s collection. The tablets had been seized by the US government during World War II while dry-docked in New York, where they were being stored by a German archaeologist, and declared “alien property” (that is, belonging to an agent of the Nazis). The tablets, of course, didn’t belong to Germany any more than they did to the US, and Tabet, a Lebanese national whose great-grandfather had worked on the dig that excavated them, was interested in asking questions about provenance and ownership that might complicate our encounters in the gallery. As war raged in Syria, the exhibition reminded viewers that violence in the Middle East hasn’t always begun (or ended) there. Western institutions were directly implicated.

Through very different means, Diyabanza and Tabet were both pointing to the ways that sculptures have historically been treated like people–that is, like property. The legal structures that permit or prevent the movement of works of art are not dissimilar to ones that impede, allow, or force human beings to cross borders. Understanding these similarities and learning to spot them in the spaces where we look at art might help us create more equitable systems to govern shared culture, and ultimately, shared humanity.

This is the beginning of what Bénédicte Savoy has called “a new relational ethics.” When we met in New York last April, the art historian and activist had just published Africa’s Struggle for its Art, an account of the research she conducted at the behest of French President Emmanuel Macron. During a November 2017 speech in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, Macron proposed that his country find a way to return the art they had stolen during the colonial era. “I want over the next five years to bring together the conditions to temporarily, or permanently, enable the relocation of African heritage to Africa,” he said. A commission was formed, led by Savoy and the Senegalese scholar Felwine Saar. Over the course of a year, they completed an exhaustive study of all the African objects in French public collections, and in November 2018, released a landmark, 252-page report that, in addition to a comprehensive inventory, argued for their full restitution.

There are passages of the report that read like poetry. “To fall under the spell of an object,” Saar and Savoy write, “to be touched by it, moved emotionally by a piece of art in a museum, brought to tears of joy, to admire its forms of ingenuity, to like the artworks’ colors, to take a photo of it, to let oneself be transformed by it: all these experiences—which are also forms of access to knowledge—cannot simply be reserved to the inheritors of an asymmetrical history, to the benefactors of an excess of privilege and mobility.” If art really is shared culture, it must be accessible to all. That means it can’t live solely in places where young Africans won’t be able to see it. It also means that the stories we tell about art can’t be asymmetrical either.

Savoy was hired by Macron’s government because she had distinguished herself as one of the leading European provenance experts while on the board of the Humboldt Forum, a museum in a reconstructed Prussian palace in the center of Berlin. In July 2017, she abruptly resigned from the board, comparing the museum to Chernobyl and telling Süddeutsche Zeitung that the origin stories of the African objects in the museum had been sealed up “under a lead roof like nuclear waste.” Even now, the provenance information that exists on the museum’s labels reads like a litany of colonial atrocities: “I had the impression to be in something like a memorial for burned villages,” she told me. “It’s very brutal, and these beautiful objects are mute. They are now only the testimonies of massacres.” The challenge, therefore, is not simply to acknowledge trauma but to find a way to move past it. To see the object, like an individual, as whole.

No one is better suited to study that whole than those who have always perceived it. “A new relational ethics begins with the recognition of the ability of the people from heritage communities to interact with their own culture,” Savoy told me. “According to this view, restitutions are not the end of a process, but the beginning of a new kind of interaction with the former, and proper, owners.” In other words, returning looted artworks actually permits more comprehensive scholarship. Restitution also allows African institutions to lend and borrow the way European and American museums do, so that scholarly exchange can flow in both directions. In November 2021, 26 objects that had been pillaged from the royal palace in Abomey in 1892 were removed from the galleries at Quai Branly and returned to the Kingdom of Benin. At a reception in Cotonou, Benin, to celebrate their arrival, Beninese President Patrice Talon declared that the occasion marked the “return to Benin of our soul, our identity.” It was also the first significant victory in Savoy and Saar’s campaign.

A century of trauma still lives in those objects. It can never be erased. But situated in new galleries under the auspices of the Benin Kingdom, the artworks can now tell new stories–or much older ones. Their import will no longer be defined by colonialism.

The debate over restitution that has rocked institutions across Europe and America over the past few years is not simply a debate over who owns culture, or where it can rightfully be displayed. It’s a debate about power in a post-colonial world where reparations can still seem generations away. Conversations around racial justice, particularly following the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, may have spurred the Smithsonian’s decision, in November 2021, to return the Benin bronzes in their collection. Nonetheless, the lack of public accountability for US institutions like the Smithsonian and the Met, which receive only a small portion of their funding from the state, means they can still equivocate. The Met, for their part, have returned a number of objects over the past two decades–including a pair of key Khmer sculptures – but only when the evidence of looting was incontrovertible, and international law was on the petitioner’s side. Private museums, meanwhile, accountable only to their boards, can avoid the restitution question altogether.

How sculpture is acquired and how it is displayed can tell us everything about the flows of money and power that shape our cultural institutions, and by extension, the world in which we live. As a body, it’s a powerful proxy for our body politic. It can help us understand historical trauma, but also learn how to better dress its wounds.

Evan Moffitt is a writer based in New York. He is the creator and host of Precious Cargo, a podcast about the journeys of works of art. His work appears often in frieze, where he was formerly Senior Editor, and has been featured in various other publications, including Aperture, Artforum, Art in America, Art Review, 4 Columns, and The White Review.

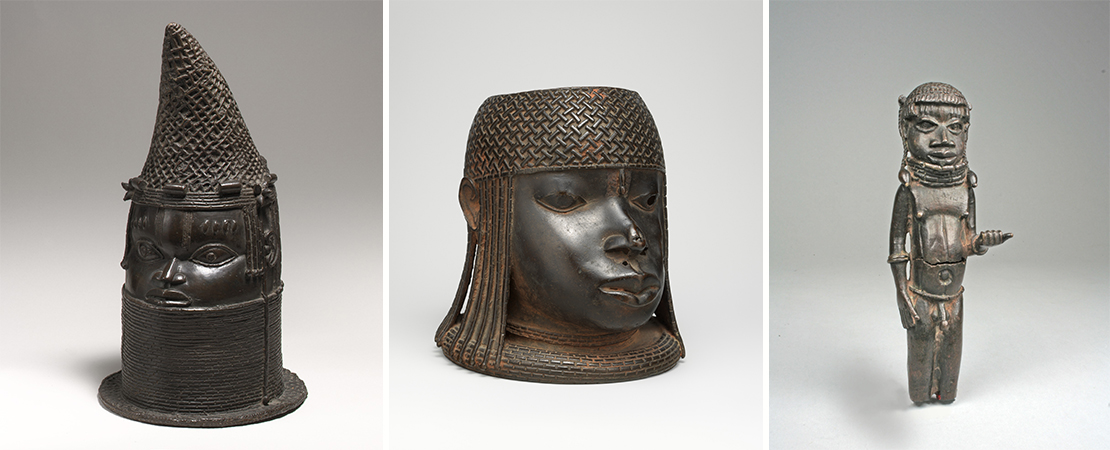

TOP, LEFT TO RIGHT: Figure: Horn Player, Edo artist, 1550–1680. Nigeria, Igun-Eronmwen guild, Court of Benin. Brass, 24 3/4 x 11 1/2 x 6 3/4 in. (62.9 x 29.2 x 17.2 cm). The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1972. / Head of an Oba, 16th century. Nigeria, Igun-Eronmwen guild, Court of Benin. Edo artist. Brass, 9 1/4 x 8 5/8 x 9 in. (23.5 x 21.9 x 22.9 cm). The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979. / Head of an Oba, 19th century. Nigeria, Court of Benin, Edo peoples. Brass, 13 1/4 x 10 3/4 x 11 1/8 in. (33.7 x 27.3 x 28.3 cm). Bequest of Alice K. Bache, 1977.

MIDDLE: Edo Artist, Queen Mother Pendant Mask: Iyoba, 16th century. Ivory, iron, copper, 9 3/8 x 5 x 2 1/2 in. (23.8 x 12.7 x 6.4 cm). The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1972. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

BOTTOM, LEFT TO RIGHT: Head of a Queen Mother (Iyoba), 1750–1800, Nigeria, Court of Benin, Edo peoples. Brass, 17 x 8 7/8 x 10 1/2 in. (43.2 x 22.5 x 26.7 cm). Bequest of Alice K. Bache, 1977. / Head of an Oba, ca. 1550. Nigeria, Court of Benin, Edo peoples. Bronze, 8 1/2 x 7 3/4 x 8 1/8 in. (21.6 x 19.7 x 20.6 cm). The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1972. / Figure: Male Attendant, 18th century, Nigeria, Court of Benin, Edo peoples. Bronze, copper, 7 x 2 in. (17.8 x 5.1 cm). Bequest of Alice K. Bache, 1977.